Teaching How to Organize Essay Writing

It is not so easy to teach students (or to motivate them) about organizing their essays from the start. This blog post is the first of two that shows you how to teach it using the magic of chunking ideas with the BEER model.

It is not so easy to teach students (or to motivate them) about organizing their essays from the start. This blog post is the first of two that shows you how to teach it using the magic of chunking ideas with the BEER model.

What is chunking and why do we do it?

Why is it so difficult for students to learn how write an essay that is organized and clear? I have been teaching university level biomedical and life sciences students this process for many years, and a key issue is that organized writing starts before the actual writing begins. Organized writing requires organized thinking, and a surprising number of students do not know what organized thinking is.

Chunking — organizing ideas into bite-size chunks where little ideas fit inside bigger ideas — is an easily understandable way to communicate to students how to organize their thinking. In daily life organized thinking is an intuitive process, but when writing, students should learn that chunking ideas explicitly, such as with an outline or mind map, is an essential part of the planning and organization process. The key to selling planning and organization to students is by stressing that it is extremely useful when you have a longer writing task with lots to do. This is doubly true in an assignment where there is both research and writing, because these are often done separately, which makes it all too easy to lose track of what you are trying to write about when you are reading about new things.

Chunking ideas makes written communication clearer for both the writer and the reader. Chunking is what creates a logical progression of thoughts. This makes it easier for the reader to understand, because the reader knows what to expect, and where each idea fits in. In the biomedical sciences, the traditional headings of Introduction, Methods, Results and Discussion (IMRaD) are examples of how important it is for the reader to be able to find what they are looking for in a text. Other headings may be more appropriate for other types of writing, but my point is that communicating the broad structure of ideas is as important as having the ideas in the first place. For the same reason of logical progression, chunking also helps the writer. Chunking helps the author to decide what to include, and more importantly, what to leave out.

How to chunk ideas in a paragraph: the BEER Model

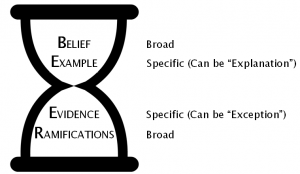

Like most elements of communication, chunking is not a right-or-wrong process. It is subjective, and at some level intuitive. Chunking is a process that works hand in glove with idea generation; that is when you should teach it, along with mind mapping and creative strategies. When teaching writing, chunking a small set of ideas (like a paragraph) is easier to explain before chunking an entire essay. I use the BEER model to explain chunking in paragraphs. The biggest chunk in a paragraph is your conclusion, which I often describe as a Belief (the B in BEER); some people call this a “claim”. In a paragraph this will usually be your first or last sentence. When organizing ideas, the Belief or conclusion is the highest level chunk. The belief or conclusion is the team captain, and all the other ideas and facts that are presented should support the team captain’s goals. A key aspect of your belief is its Ramifications (the R in BEER); I like to explain to students that ramifications are what gives meaning to your belief; the ramifications are what answer the questions, “So what? How is our understanding of the world changed by this belief?” Each ramification is a medium level chunk inside the belief, and a major ramification will usually lead to the next conclusion or belief. Inside of the belief are other ideas and facts that support it, such as Evidence and Examples. Each example or piece of evidence is a small size chunk. Some pieces of evidence have Exceptions, and these are tiny chunks provided to the reader to prove that you also know the weaknesses of your own argument. Throughout this pyramid of ideas there are Explanations, and each explanation fits inside the belief or argument it is explaining. The final aspect of the model is explaining about digressions; a digression is often an interesting fact or idea, which may even be related to your topic, but a digression is an idea that does not serve the purpose of supporting your belief or conclusion.

Like most elements of communication, chunking is not a right-or-wrong process. It is subjective, and at some level intuitive. Chunking is a process that works hand in glove with idea generation; that is when you should teach it, along with mind mapping and creative strategies. When teaching writing, chunking a small set of ideas (like a paragraph) is easier to explain before chunking an entire essay. I use the BEER model to explain chunking in paragraphs. The biggest chunk in a paragraph is your conclusion, which I often describe as a Belief (the B in BEER); some people call this a “claim”. In a paragraph this will usually be your first or last sentence. When organizing ideas, the Belief or conclusion is the highest level chunk. The belief or conclusion is the team captain, and all the other ideas and facts that are presented should support the team captain’s goals. A key aspect of your belief is its Ramifications (the R in BEER); I like to explain to students that ramifications are what gives meaning to your belief; the ramifications are what answer the questions, “So what? How is our understanding of the world changed by this belief?” Each ramification is a medium level chunk inside the belief, and a major ramification will usually lead to the next conclusion or belief. Inside of the belief are other ideas and facts that support it, such as Evidence and Examples. Each example or piece of evidence is a small size chunk. Some pieces of evidence have Exceptions, and these are tiny chunks provided to the reader to prove that you also know the weaknesses of your own argument. Throughout this pyramid of ideas there are Explanations, and each explanation fits inside the belief or argument it is explaining. The final aspect of the model is explaining about digressions; a digression is often an interesting fact or idea, which may even be related to your topic, but a digression is an idea that does not serve the purpose of supporting your belief or conclusion.

If your students do not have the hang of it, you can ask them to do an exercise. Exercises on organizing thoughts should start simple. The exercise should entail no research, and it should be based on knowledge they already have. The process is intuitive, so you should ask them to write something they can approach intuitively. Before they begin you should also explain that there are no right or wrong answers, but some answers are better linked together than others

Exercise 1: Write a paragraph

15 minutes of student time + time for feedback

Write a paragraph (on any open-ended topic) with a line between each sentence and label each sentence as:

· Belief

· Ramification

· Evidence

· Example

· Explanation

· Exception

· Definition

· Digression

Possible topics:

“What is the meaning of breakfast?”: include “pizza for breakfast” and “breakfast served all day”

“Are viruses alive?”: include “replication” and “parasitic/dependent existence”

Next week: “How to chunk ideas in an essay”